Editor’s note: In the series, we ask 13 interesting people to consider a work of comic art and tell us what it means to them. They can focus on the the character, the history, the artist, the context, how it makes them feel…heck, even how it doesn’t make them feel.

For our fourth installment, we welcome the Jack Beltane, author of Penny Harper and The Toyland Tales.

That’s a lot of words. The title certainly grabs me—“tales” and “suspense” being two words sure to catch my eye—but then my eye travels down the page.

I’m not a fan of talky comics, which I realize sounds weird, but here’s the thing: If I want words, I’ll read a novel. To me, the beauty of comic books is that they use visual storytelling. Sure, words are necessary—no one likes a mime—but in comics, they should be used sparingly. That is what puts equal weight on the artist and the writer in the medium: The artist has to fill in everything but dialog with images, like a movie, and the writer has to not cover up the artwork with monologues.

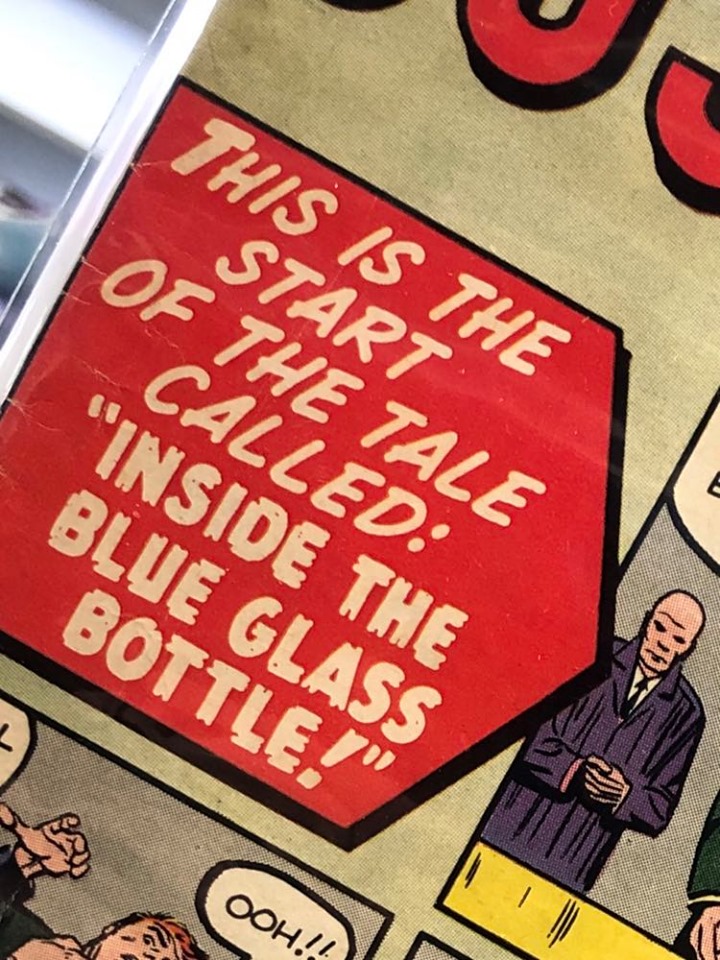

Tales of Suspense #34 gets off on the wrong foot with that big red arrow that contains a full sentence. More than that, a sentence that requires internal punctuation (the colon). Furthermore, “Inside the Blue Glass Bottle” is, well, sort of a flat title. I’m kind of bored already. That is a lot of words and a dull title.

I try to be an optimist, however, so I’ll give it the benefit of the doubt. Maybe they needed to put a seven-panel page on the cover—with words in every panel—because the story is so amazing, it couldn’t be easily summarized. You know, I have trouble writing titles and headlines, too. When I worked at a newsweekly, I never wrote my own headlines because the copyeditor could do it much better and much more quickly. It’s that whole “use words sparingly” thing again—it’s a different kind of writing.

So I read the cover and am unimpressed. I know this is an early silver-age book and my expectations should be different, but dang it—nobody talks like that! These classic villains are parodied for everything that is wrong here: The writer uses “dialog” as exposition instead of letting the artist fill us in on the facts. This guy is apparently evil and can shrink people, so why is the actual shrinking of the man done “off camera”? Are we to assume the artist didn’t know how to visually represent “evil wizard shrinks a guy”? This is a vital clue to the fact that this book is not going to use the artist well, and the writing I have seen does not fill the gap.

It’s a pass for me. I don’t even think I’d flip through it. That final starburst sounds like a sales pitch from a cheap huckster who knows it’s a load of crap, and that kind of thing keeps me moving right along.

My take is that golden- and silver-age books are “gold and silver” not because they are the pinnacles of the art form, but simply because they came first. I’d say we’re actually in the true golden age now. Sure, there were always great visual storytellers, but we didn’t truly move away from wordiness in “mainstream” comics until the late ’90s, with things really bubbling up around the first Marvel Civil War. Comics—the great ones—have a hit a highwater mark only in the last two decades, with the emphasis on art and words working together to show you a story—like a movie—instead of telling you one with word bubbles that fill entire panels.

In fact, there is nothing I love more than a page or two with absolutely no words; those are the moments I feel fully immersed in the action. To use the curmudgeon from It’s a Wonderful Life as a metaphor for showing instead of telling, consider this line: “Why don’t you kiss her instead of talking her to death?”

Exactly, evil wizard: Why don’t you just shrink the guy instead of talking him to death?

Jack Beltane is a novelist who uses way too many words to tell stories about the interesting lives of ordinary people. He’s also a big fan of silent movies. Look him up at jackofbells.com.

Leave a Reply