Editor’s Note: In my past life, I used to spend some time talking about poetry in classrooms. One of my favorite poems to offer classes was “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird” by Wallace Stevens. In that poem, Stevens basically writes thirteen mini-poems, all ostensibly–you guessed it–about blackbirds.

I liked using this poem because on the surface, it’s not really about anything; since I was often talking to people who weren’t necessarily die-hard poetry fanatics, I could use the poem to talk about how poetry doesn’t really have to be about secret meanings. Sure, you could try to wring some deeper understanding out of it later on, but you could just as well look at Stevens’ poem and say, “Man, this guy was really hung up on blackbirds!”

The poem also lends itself to a quick creative writing assignment. I could tell the class to look around the room and pick any non-human object and write 13 quick things about it. In fact, you can try this yourself right now, wherever you are! If you need some inspiration, here’s the last stanza of the poem. No Spoiler Alert necessary!

XIII

It was evening all afternoon.

It was snowing

And it was going to snow.

The blackbird sat

In the cedar-limbs.

And that’s it. There was no spoiler alert because, really, if there is some deeper meaning in the poem, I don’t know what it is, and honestly, I don’t care. For me, poetry is often ruined by caring about the meaning. I sometimes just want the experience. It has often been my contention that forcing students to look for meaning in poetry ruins the entire point of poetry, which is simply to offer some human connection, a version of how the world seems to us at a particular moment. We can do the poem a disservice worrying about what the poet wants us to think, or feel, or understand. While all those things matter, to me they don’t matter at this moment. I’ve read this poem hundreds of times, but only today did that last section matter to me, because only after the last month of Covid-19ism could a line like “It was evening all afternoon” strike me this particular way.

And with that, we introduce a new series, called 13 Ways. In the series, we’re going to ask 13 interesting people to consider a work of comic art and tell us what it means to them. They can consider the character, the history, the artist, the context, how it makes them feel…heck, even how it doesn’t make them feel.

We give them the art, and they give us what the art means to them.

First up, we have the Sanctum Sangiacomo’s very own Purveyor of Poetry, Mike Sangiacomo himself:

1. The First Way

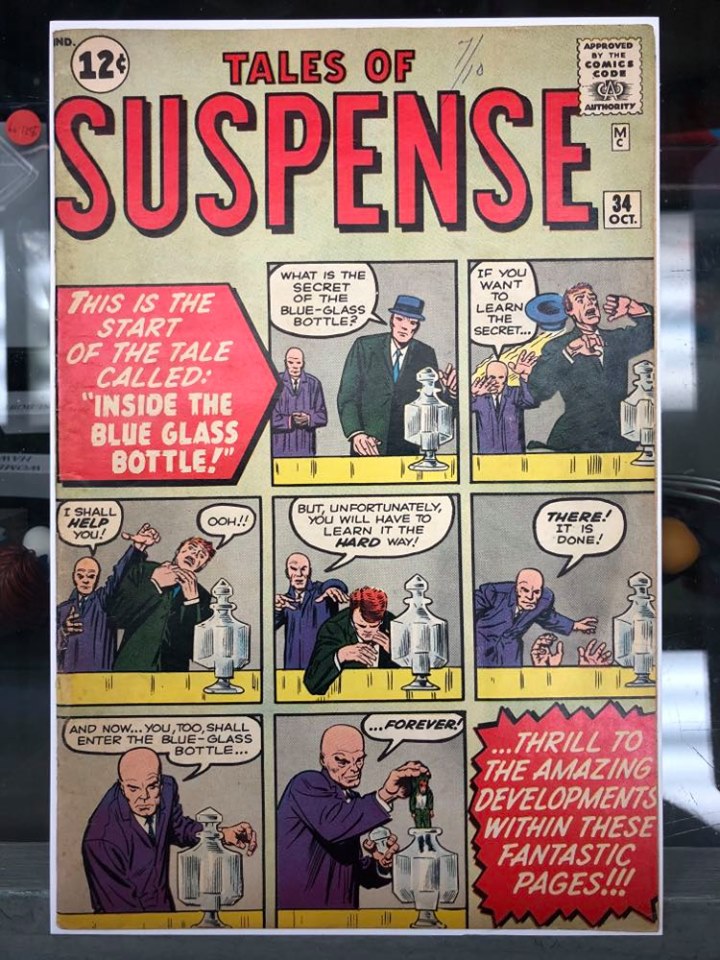

The cover of Tales of Suspense #34 (1962) is a bit of a journey into mystery itself.

Even back then, comic publishers were well aware that they had a split second to catch the attention of a prospective reader. If the cover could just get the reader interested enough to at least pick up the book and thumb through it, there’s a chance that someone would buy it.

This cover is unusual with its nine-panel construction, including two panels with the famillar Stan Lee hyperbole. It reads, “This is the start of the tale called ‘Inside the Blue Glass Bottle!’” Only the cover isn’t that tale. The seven panels are a mini-story in themselves and do not appear in the 7-page story within.

The story was written by Stan Lee (as were pretty much all the Marvel comics of the time), with a likely scripting assist from his brother, Larry Lieber. It was drawn by the great Jack Kirby with inks by the also pretty great Dick Ayers.

This comic was released at a crucial time in Marvel history, just as the company was slowly moving into superheroes. At this time, the only superhero books Marvel had on the stands were Fantastic Four and the initial six-issue run of The Incredible Hulk. Tales of Suspense was still five issues away from entering the super-hero showdown with the introduction of Iron Man in issue #39.

So the Marvel execs were still mostly still in their monsters-cowboy-teen-girl phase as they closely scrutinized the sales reports of the FF and Hulk. Were they really going to change everything and drop the monster-of-the-month formula and switch to superheroes?

My guess on the genesis of the “Blue Bottle” story is pretty simple. Marvel was probably trying just about anything to sell its books. Stan would have given Jack a quick rundown of the story, something like, “A guy walks into a curio shop and gets trapped in a cool blue glass bottle.” Jack would take that idea and run with it. It’s impossible to say who had the idea to turn the cover into a mini-comic with a complete (and different) story.

On the cover, the shop owner apparently has some magic powers that shrink the hapless customer and plop him into the bottle. Not only are the circumstances around how the guy ended up in the bottle totally different in the inside story, but there is no hint that the bottle already contains a beautiful woman, a major plot point of the full story.

Interesting to note, the bad guy looks a lot like the Fantastic Four foe, the Puppet Master (Phillip Masters) and, like many monster comics of the time, the woman looks like Susan Storm and the hero resembles Reed Richards, right down to the professorial jacket and pipe.

Also, the shape of the bottle is completely different from the one on the inside story.

This brings up a chicken and the egg question. Is it possible that Jack drew the cover as a one-page filler piece that ended up inspiring a full story, albeit a short one? Or was it always meant to be a cover?

The layout of the cover is certainly different: I can’t remember any other covers like it at the time. Marvel had a few covers that were divided into two or three panels, but none featuring as many as this. The cover of Tales to Astonish #28 features a six-panel breakdown (including the blurb panel) for “I Am the Gorilla Man,” done by the same team.

At some point in time, I bought that issue, though not off the newsstand. From the newsstand, I did buy the Fantastic Four and Hulk issues.

Speaking for myself, by that time I had gotten pretty bored with the Marvel monster books. They were fun, but tended to feel very similar especially since Jack used the Reed and Sue Richards models for many of the stories. Decades later, a writer, (John Byrne maybe?) wrote a story where the hero of one of those monster books actually was a pre-FF Reed Richards.

Bottom line, the cover was interesting but not enough for me to spend 12 whole cents on.

Let’s not get crazy here.

When he’s not busy curating the Sanctum Sangiacomo, Mike Sangiacomo is a reporter and author of comic books, including Phantom Jack and Tales of the Starlight Drive-In. He lives in Amherst, Ohio.

IF you would like to read “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird” in its entirety, here’s a link: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45236/thirteen-ways-of-looking-at-a-blackbird

Leave a Reply